Executive Director, The Mori Memorial Foundation

Urban Development × Area Management:

Experts from London and New York offer Tokyo insights on city creation

Roppongi Academyhills Towerhall

Executive Director, The Mori Memorial Foundation

Introduction: Urban Development and Area Management

Ichikawa

Urban development and area management

London continues to demonstrate increased vigor even after the 2012 Olympic Games through steady growth and the likely successful completion of new urban renewal projects. New York is substantially improving the quality of its parks and roads through collaborative efforts between the public and private sectors, all the while breaking down preconceptions about public spaces. So what can Tokyo learn from these cities in order to become the world’s most appealing city? After analyzing Tokyo’s current urban strengths, let us consider the city’s future with reference to London’s latest urban development projects and the topic of area management in Manhattan.

Analyzing Tokyo’s urban strengths

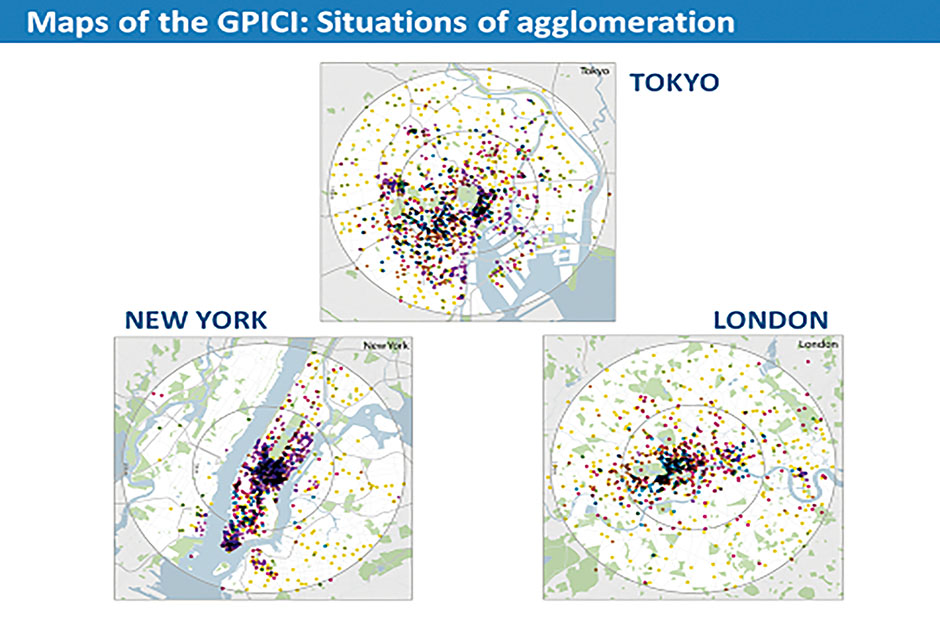

To gain an understanding of Tokyo’s present day urban strengths, we need to analyze the city from multiple angles. The Mori Memorial Foundation’s Institute for Urban Strategies has analyzed Tokyo in its three city indices, namely, the Global Power City Index (GPCI), the Global Power Inner City Index (GPICI), and the Global Power Metropolitan Area Index (GPMAI). Today, however, I would like to talk about the GPICI, which selects eight leading global cities and analyzes and compares the urban power of their 5km and 10km inner city zones. The cities are assessed on a total of 20 indicators across six key inner-city properties: Vitality, Culture, Interactivity, Luxury, Amenities, and Mobility.

We should first turn our attention to the number of the “World’s Top Companies.” After plotting on a map of Tokyo the head office locations of the firms listed in the Fortune Global 500 in 2015, we can see that 37 companies are based within the 10km inner-city zone, more than any other city. This certainly highlights Tokyo’s vibrancy. In contrast, a lack of cultural facilities in central Tokyo, especially the limited “Number of Theaters and Concert Halls,” is detrimental to tourism in the city. Meanwhile, “Airport Access,” which compares each city’s accessibility to international airports from the major inner-city railway stations, reveals that access from central Tokyo to its international airports is not up to standard, suggesting a weak global network.

The overall results from the GPICI see Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Paris ranked as the top three cities for the 5km zone. For the 10km zone, Tokyo, Paris, and Hong Kong hold the highest overall scores, in that order. London and New York, with their large metropolitan areas, increase their scores to be on a par with Hong Kong. By analyzing each area, we can see that Manhattan’s midtown and downtown areas have a high concentration of urban functions that exemplify New York’s power, while London boasts many such functions in the area extending slightly westward from Trafalgar Square. In Tokyo, a high density of urban functions can be found to the east of the Imperial Palace in the area stretching down from Tokyo station to Ginza and Shinbashi. More city functions are also concentrated outside of the 5km zone towards the southwest.

Urban development projects in central Tokyo

Many of the urban development projects in the inner-city areas of Tokyo that have been implemented ahead of the Olympic Games in 2020 will approach completion in 2025. Various development projects are ongoing, including a so-called “urban chain redevelopment project” in the Otemachi, Marunouchi, and Yurakucho areas. On the other side of Tokyo Station in the Nihonbashi, Yaesu, and Kyobashi districts, many more similar development projects are underway. A project that aims to redevelop the Tokiwabashi precinct has slated the construction of a 390-meter high-rise tower that has the potential to become one of Tokyo’s newest landmarks. Even the Toranomon/Roppongi area is seeing a wave of construction projects, the most notable of which is a bold plan to create a new Shintora-dori avenue connecting Shinbashi and Toranomon, something resembling the Champs-Élysées boulevard of Paris. In Shibuya too, large-scale urban redevelopment is being carried out with the construction of three new buildings, including the refurbishment of Shibuya Station, which is all part of the Shibuya Station Precinct Development Plan. In the bayside suburbs of Toyosu, Harumi, and Ariake, where much of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics are set to take place, sporting facilities and athlete villages are currently under construction.

Trends in area management in central Tokyo

In addition to Tokyo boosting its urban power through development, since the year 2000, at least 70+ local organizations have become very active with regard to area management in inner-city districts. Area management can be broadly classified as either “Large-scale Development” type that centers on large, new projects, or “Existing Built-up Area” type. Furthermore, the latter type of area management can be split into three categories: 1) “Shared Vision” whereby all-inclusive management and administration plans are shared, 2) “Platform” that loosely connect various organizations, and 3) “Existing Community Area” through which a common organization is created on the premise that the existing community has its own identity. The area around Roppongi Hills is a good example of large-scale development-type area management. The area management implemented in Otemachi, Marunouchi, and Yurakucho is based on vision sharing, while a platform-style of area management is being adopted in Nihonbashi. Area management that best suits the respective characteristics of these places is being implemented and is helping to enhance Tokyo’s appeal even from an urban management point of view.

Infrastructure of Inclusion: The London Model

Burdett

Densities of cities

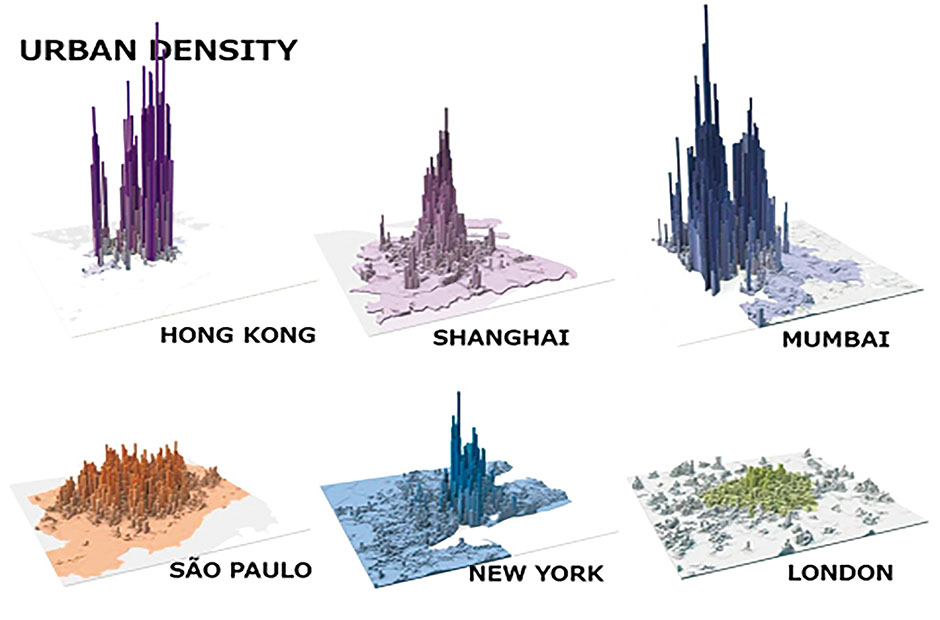

From a viewpoint of density, Tokyo is a relatively low rise city. Most of the buildings are about five to eight stories high. However, Tokyo is actually one of the densest cities of the world. London, by comparison, is a relatively dispersed, low-density city. New York is much denser than London.

These issues have enormous impact in terms of the economy, as seen in the agglomeration effects. If we look at where people live in London, they live in low density areas. If we look at where people work in London, a huge number of people come into the CBD (Central Business District) on a daily basis. As can be seen in the map of New York, Midtown and Downtown show a higher density in terms of population, and even more people are coming into New York. The increase in population requires a good transport system. New York has a better transport system than in London. Tokyo has one of the best examples in the world.

Pointing to the east

The whole of London is moving eastwards. The area along the river Thames has been redundant, enjoying an enormous opportunity to grow, improve, and invest. However, there are other reasons why this area is considered to be important.

As the diagram of London’s “Index of Multiple Deprivation” shows, the east of London is deprived with lower life expectancy, higher unemployment, and lower levels of education, and the west is in a better state with some exceptions. Therefore, if people want to initiate something to make London more equitable, more livable, and better to grow up and to be educated and to work in, they need to deal with this “east / west divide”.

DNA of London

What distinguishes London is that an urban planner, Patrick Abercrombie, decided that the city should have a green belt. A very large area of protected countryside was created around the city. This is a fundamental aspect, the DNA of London. The London Plan estimates that London is going to grow by about a million people in the next decade and a half, and it must grow within the existing limits. It only allows developments in special areas where there are good public transports.

Changes happening in London

Not everything is perfect. In the City of London, our real historic 2,000-year-old CBD is more or less changing. Today, some buildings which do not look necessarily attractive are actually being built. The important issue is not only how these buildings meet the sky, but also how they meet the ground. That is what makes a piece of city work or not work.

One of the best connected areas immediately to the north of London is next to two railways stations, St. Pancras and King’s Cross, which have been reinvested by the railway companies. This big empty ex-railway area is now being transformed into a mixed-use development with universities, research facilities, and other commercial properties. The whole project was designed around a network of ground floor public spaces, one of which has already become the most used public squares in London.

2012 London Olympics and beyond

The Olympics has been an interesting experience for us. The whole plan was designed not only for 2012, but also for transforming the Olympic Park. It was essential to think about what it will be like in 20-30 years ahead. At the heart of this plan was a notion that a major new park should be built for east London, which has been the most deprived part of the city. Therefore, providing a park, a velodrome, and a swimming pool was considered as social services, improving the livability of the area and communities. This is where public money really makes a long term value as it makes the city more balanced. We are very much thinking about how this might work in terms of extending London eastwards around the river to accommodate growth over the next generations.

Times Square Transformation: A Public Space Journey

Tompkins

Times Square 1.0: Safety and Security

Times Square, named after the headquarters of the New York Times, has been around for a hundred years, and is known for being a gathering place on occasions like New Year’s Eve. As a public space, it has been dominated by cars and by the intersection of two major avenues for a long time. By the 1970s and 80s, it was one of the most dangerous places in America. The public sector was so desperate to change it that they almost destroyed Times Square in the process of fixing it, by initially neglecting to preserve its authentic and distinctive characteristics, such as its historic theaters and its dynamic signage. Only the intervention of civic groups changed that.

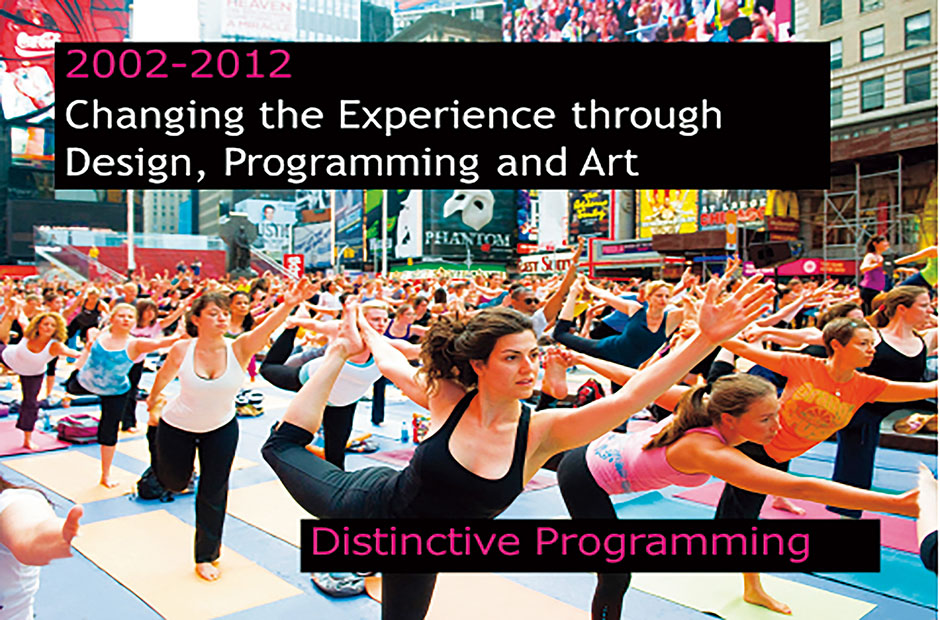

When the Times Square Alliance was created in 1992, the property owners focused on the basics of public space management. At that point, this was about making it clean, safe and friendly. It was not until 10 years later that we were able to focus on higher level public space problems concerning creativity and authenticity.

We began by trying to change perceptions through partnering with entities for events like the New Year’s Eve celebration. Fundamentally, we were focusing on sanitation and on clean streets. We were working on issues of homelessness by partnering with experienced NGOs. We also partnered with Broadway to take the theatrical talent out onto the street as a way of showing that the public spaces could be viable. We played the very important role of placing people wearing uniforms on the street. They were not police with the power to arrest, but were the eyes and ears on the street paying attention to smaller, quality-of-life crimes.

Times Square 2.0: Public Space Transformations

We talked about the importance of the pedestrian environment, because the pedestrian congestion that grew out of success made Times Square a far less pleasant place. At the same time we laid out a set of principles, the most important of which was to make it a place to which New Yorkers would want to come. Duffy Square, where you can get discount tickets, was the only public space in Times Square besides the sidewalks, and it was dysfunctional and ugly. We set about trying to create a new paradigm and show what we meant with all these ideas about constructing a new public space.

In 2008, we, together with our partners at the theater development fund, placed bleacher-like stairs in the plaza (TKTS). Part of the reason it worked is because the design was responsive to the core characteristics of the location. The steps mimicked a Greek amphitheater and thus referenced a core characteristic of Times Square: its theaters. They also glow at night, referencing another characteristic of Times Square: the digital signs. Now the plazas are being built into a better space. They are about 3/4 done.

Suddenly, we had an overwhelming amount of aggressive commercial activity. The worst examples were people dressed up as Mickey Mouse or Cookie Monster, who would be very aggressive with visitors in the public spaces. The public space in Times Square, once again, was going out of control. We proposed a plan to regulate some of this aggressive commercial behavior, but not to ban it entirely.

Times Square 3.0: Vision for Times Square

Now the question is “What is the creative and cultural vision for Times Square,” and, by extension, “for the public realm in New York City?” This is a series of questions that you can ask about any space between buildings, any public space. Part of the answer for us is a town square that is thriving, that looks good and is well-managed, that balances, as great cities do, both commerce and culture, the past and the future. And the space should reflect the best of the community where that public space lies. For us, it is New York City, but we also reflect over the world.

So we have been working on a proposed set of Principles and Admonitions of the Times Square Alliance to guide us. For example, that the city should always be changing, but it should not forget what connects it to the past. Be commercial, but don’t let commercialism overwhelm the civic activity. Curate original programming, but also allow for the unexpected and the spontaneous. Let it be transparent and open, but not so open and so free that it is totally out of control and a free for all. And welcome the visitor, but most importantly, make sure the local, the New Yorkers, feel it is theirs.

A key part of creating a great public space is to know thyself and love thyself. You need to know what is distinctive and authentic about your place, what sets it apart from other places. And then, you have to love and nurture that. As you explore what your essential characteristics are, do not be driven only by intuition, but also by facts and analysis, which will also help you to frame your communications and advocacy as your strive to nurture your essential assets.

So, if you are trying to create change, if you are going to have critical mass, it needs to start with the community. Sometimes that community is channeled through an organization like ours, and sometimes others. It needs to be consistent over time. It needs to be coherent and part of a plan. This is a model for changing public spaces or other areas. It needs to be concentrated, not dispersed. Throughout it all, it needs to be creative. If you do those things, then you end up with something that is true and authentic. Ultimately, the end result is a place that is more attractive, although not always in a conventional way. And it may well also be just a bit crazy and unpredictable, which is after all, part of what we love about our cities and great urban places.

Remaking New York Today

Kimmelman

Housing issues in New York

New York is a very expensive place to live. New York is largely unaffordable to many of the people who make it run, who give it its life blood, and who have often been there for many generations. Therefore, the major initiative of Mayor Bill de Blasio is to create more affordable housings in a way that we incentivize private developers by giving them tax breaks to add affordable apartments to their projects.

In Brooklyn, there are a lot of public housing and open spaces which the city hopes to convert into new housing projects. One of the problems is that you are concentrating poverty because there are very few people who will choose to live here, as there are very few market rate apartments. While the city has been contemplating how to develop some areas in east New York, real estate speculators have already been buying properties there, raising the value of land and pricing out some of the very poor people whom the new policy is intended to protect.

The people in east New York do not see housing as a neighborhood. They want the things that make a neighborhood such as a new library, new parks, and better schools. The question is how to plan neighborhoods in a holistic way.

The Plaza Program

The Plaza Program in the city does not only include Times Square but also many other plazas around the city. At Pearl Street in Brooklyn, attempts have been taken to improve some space of the street that had been used for parking or was more or less disused. So they painted it, added some benches and some potted plants, and turned into a place that people could take over to pedestrianize it. These attempts have had enormous success throughout the city and are part of what I think is another very large issue which this administration is not focused on. This is about rethinking the streets completely, not just in terms of pedestrianizing them, but also thinking in terms of future driverless cars. We should think in terms of how we can reclaim the city for bikes, flip the priority away from the car, and reclaim these spaces for better use for pedestrians and people.

Big U project

The Big U project is a part of the post-superstorm Sandy resilience initiatives funded by the federal government. The plan is headed by Bjarke Ingels and his firm called BIG. The proposal is to make approximately 10 miles of the Lower Manhattan coast greener and more resilient. It actually stretches all the way around the southern end of Manhattan, shielding the city from floods and storm water. It seeks to improve the public realm, providing new playing fields, markets, gardens and so on. It will begin in an area on the east side next to public housing projects, which have always been cut off from the waterfront by the highway, the Franklin Roosevelt East River Drive (FDR Drive). The project is essentially beginning from an idea of providing better access to people in some of the most underprivileged areas.

Skyscrapers

New York is going through a wave of new giant super slender skyscrapers, very particular to the city. There are several new towers along 57th Street with views of Central Park that will rise into the clouds, about 1,300 feet high. Obviously, it has caused a lot of concerns among some people. New York has always been a city of skyscrapers and, in fact, the buildings along the southern end of Central Park were seen as skyscrapers when they were first built. Now they are synonymous with the beauty of Central Park. That is not to defend all of these skyscrapers. Some of them are good and some of them are bad.

One of the issues that is discussed in a place like London but is never discussed in a place like New York is the extent to which the skyline is also the public realm. If someone was to put up a building that is taller than the Empire State Building today, that would change the profile of the city. They are going to change the shared asset in New York. There is a conversation to be had about how much the skyline is the public realm and what kinds of decisions should be made about what it looks like. We should participate in the same kind of conversations that happen for other aspects of the public realm: our parks and our streets. And I think these new skyscrapers may possibly initiate this conversation. At least we can start it now.

Panel Discussion

Ichikawa

New York, London, and even Tokyo currently face similar challenges, but the nature of those challenges differs considerably if we think beyond the year 2025. The difference stems from population. Both London and New York are planning for the future based on the premise of population growth, but Tokyo’s population is predicted to decline sometime after 2025. Thus, I would like our discussions to take into account these differing assumptions.

In New York, the construction of “supertall” skyscrapers in Midtown Manhattan has already begun. In London, however, much shorter buildings are going up in order to entwine the historical fabric of the land on which they stand, as typified by the King's Cross Project. So in light of these trends in New York and London, what kind of future vision should we project for Tokyo?

Kimmelman

It is certainly true that a new group of skyscrapers are redefining the skyline. The distinctive two humped Manhattan skyline is going to be modified. But the real change has happened on the ground, and it has nothing to do with the skyscrapers. So the question is what kind of neighborhood is being created by these new buildings.

Burdett

The key point is why are we so obsessed with tall buildings? Why is this such a big issue in discussing the future of cities? Ultimately, whether the building is tall or thin or has a pitched roof or whatever is part of the public realm of the city. It is important to design buildings for the future in a way that they respect the DNA of what the physical grain is and what the social grain is.

Tompkins

I want to comment on some of the similarities, which is the fact that urban life is becoming more popular. And even with the demographic issues in Tokyo, assuming these cities stay safe, they are continuing to be places to which people want to go. But I think a core factor that we have in common is that, as the world becomes more urbanized, there is an economic pressure of things getting more expensive because more people want to go to cities. It is important to address it.

Another issue that I just want to comment on is that my initial impression of Tokyo is a sort of mix of order and disorder. Visually, at first, it seems like there is not a master plan to Tokyo and there is a sort of disorder in what is there, but I discovered an amazing order within that disorder. I think that, whether it’s Time Square or any city, there is this tension between order and disorder and control and letting go, and market forces and civic purposes that run through every part of what cities struggle with.

Ichikawa

Times Square in the 1970s and 80s was an unsafe place to visit, but it is now brimming with people. Those who know what it was like back then are amazed at its transformation. How do you see its future unfolding?

Tompkins

One of the basic things is simply creating more space for people. It is not a matter of getting more people to Times Square, but it is an issue of how do you engage them in the public space, especially around the margins, as at times like midnight. And the larger challenge is that there are many people that say Times Square has lost its soul. It is a metaphor of the situation where, as the city becomes more expensive, it becomes important to think of how to bring life and creativity to it. Part of what we are experimenting with in Times Square is how to bring in creative people and artists to help people see the place in a new way and to bring life to it.

Kimmelman

Times Square has become extremely crowded and this is part of the problem. The plan to change it through pedestrianizing it is yet to be completed. So a lot of the hostility towards what has happened there is really not taking into account what this is going to be like in the near future. Certainly, the character of Times Square will change when the project is actually finished.

Burdett

I think so much of what you are describing is recognizing the importance of “time.” One needs to think of what happens from six in the morning until ten or eleven in the evening or midnight and throughout the year and throughout the week. I think that is something that planners and designers have been very weak at in the last 30, 40, or 50 years. And I think that is coming back.

We are lucky these three cities got the problem of congestion. Most cities in the world are facing depopulation, or depopulation from city centers. I think the biggest challenge that we are all interested in here in Tokyo is if the population is not going to grow enormously, but you are going to be adding so much volume, you have the risk of having places that are not full. What actually happens to these spaces, and how are they programmed? And I think the lessons of Times Square are very useful. But in a way density and congestion is a good problem to have.