“Beyond 2020: Tracing the path of London’s Olympic Legacy”

Roppongi Academyhills Auditorium

Professor, Teikyo University/

Executive Director, The Mori Memorial Foundation

Richard Brown Special Lecture

Richard Brown

In discussing London's Olympic Legacy, particularly the changes adopted around the Olympic Village and the Olympic Park, it is first important to understand the bid process, and the conditions in London in the years leading up to the Games.

London was declining as a city until the mid-80s, at which point the population reversed a long downtrend. This downtrend was partly due to public policy which moved industry and people out of the capital city and partly through the global tendency for people to migrate out of large cities in the 1960s and 1970s.

The reversal, though, driven by financial services, cultural revival, and more open borders, has led to London’s population reaching over 8.5 million with an expected 10 million by 2040. The city's strategy for dealing with this growth is expressed in the Mayor’s London Plan, where the eastern areas around the former docklands and former industrial areas of the Lower Lea Valley and Thames Gateway have been the focus for redevelopment.

In 2005, these areas comprising the Lower Lea Valley were some of the poorest districts within the UK, and also extended over the boundaries of four different local authorities—making it difficult to address challenges due to the absence of a single responsible authority. Another challenge was that 19th-century anti-pollution legislation had sent dirty industries to the Lower Lea Valley area.

Despite these issues, there still existed a unique culture where people could grow food in allotment gardens (rented from local councils), and artist studios opened in abandoned industrial facilities. So, there was a sense of dereliction, but also significant interest, leading to an increase in new residents. This combination of factors influenced the decision to situate the Olympic bid in the Lower Lea Valley. The Olympics would be a catalyst for government attention, investment, and promotion of East London.

The final bid set out three principles for the London 2012 Games. One was that the Games would be compact. First, athletes were kept as close as possible to competition venues, partly to lower the risk of people turning up late for events. Secondly, the Games would depend primarily on public transport, to avoid attracting more vehicular traffic to London. In terms of connectivity, a key component was the New London-Paris high-speed rail line, which was used as a shuttle service taking people from St. Pancras in central London to the Olympic Park in about 7 minutes. Thirdly and perhaps most significantly, we would hold the games in a part of the city that needed investment, regenerating and transforming the area.

From the Olympic and Legacy Master Plans starting in 2008, it became integral that every venue would either have a clear plan for its reuse after the Olympic Games or it would be built as temporary. Thus, temporary venues were to be taken out after the games and either replaced with development zones to bring in new housing, or to be turned into park areas to create a larger green space. Partly through these ideas, and through the vision for transforming east London, the London Olympic bid was successful.

With plans set, how then would the Games be delivered? It was gleaned from the Sydney Games that various delivery organizations and government groups could have significant differences in opinion, leading to arguments and falling out. To combat this, an Olympic Board comprising the government, the Mayor of London, the British Olympic Association, and the International Olympic Committee, was established as an arena for resolving disputes, agreeing on plans, and for ensuring that everything remained on track.

The government, then, would set up a new Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) who would ‘build the stage’ for the Olympics. At the same time, the Mayor of London, and the IOC would set up the London Organizing Committee (LOCOG), who would ‘put on the show’. So these two organizations with different accountability would both meet at the top; they were also accommodated in the same building. Finally, from 2012, we established the London Legacy Development Corporation (LLDC), which would be responsible for the park and venues after the Olympics and transform them to their legacy uses.

The success of these structures is evident in two ways. One is the fact that these structures survived a change of Mayor of London and two changes of government in the run up to the games, and secondly that very few disputes between the two bodies arose, and fewer still became public knowledge.

Starting on the venues in 2006 and 2007, most were to be financed and delivered by the ODA, but some were planned to be constructed by private contractors, with direction from public bodies — the private sector financing, and carrying out design and construction. London would lease them back for the Olympics and then they'd be used commercially.

But due to the financial crisis in 2007, the public sector had to take on responsibility for delivering those projects itself. Fortunately, the budget had enough contingency built in for unforeseen events. Everything had to be delivered by 27th of July 2012 and having that specific date was a powerful force in galvanizing government and pushing people to cooperate.

And yet after that deadline, and the completion of the Games, there was still the transformation to undertake, including the initial takedown of the venues and infrastructure, disposal of temporary venues, and the conversion of retained venues. This was the role of LLDC.

In addition to dealing with venues post-Games, the areas surrounding venues were also a factor to consider. There existed a network of empty spaces between and surrounding venues that needed to be filled. From around 2007 and 2008 the London Development Agency, along with the legacy organizations, were working on a ‘Legacy Master Plan Framework’ conducted with architects and planners from Allies and Morrison, preparing to think of what shape the future Olympic Park would take. Housing was a primary focus in the original plan, building around 12,000 homes in large blocks around the Olympic Park and converting the park itself, making it a center for visitor attractions for people to come and spend time.

The first task was to get the venues reopened and a timetable was set that by April 2014, most of the park and venues would open. This was achieved as planned. The stadium came later in 2016, though it did face several challenges.

Regarding the transformation of the different venues and their current uses, the Copper Box Arena, which was used for range of sports during the Games has now been retained as a multiuse arena. It essentially holds everything from basketball to boxing to product launches to fashion shows, and hosted events like the wheelchair rugby championships. It has had more than 2 million visitors since it reopened in 2013.

The beautiful aquatic center designed by Zaha Hadid was a building that was clearly built for legacy and not specifically for the Olympic Games. During the Games it had two unsightly spectator wings attached to the structure, but these were removed after completion of the Games. Since then, it has been performing well as a community venue with competitive pricing. It also hosted several competitions such as the World Diving Championships, European Swimming Championships in 2016 and later this year, the World Para Swimming Championships.

The Athletes Village was actually built with public money in the end, and was eventually sold in 2011. It's quite unique in London because it's an entirely rented development with 50% allocated to affordable rent. The building has been fully occupied since the day it opened up and it now acts as the first residential community in the park.

The stadium is a more complicated story that reveals important lessons related to decision making for Olympic hosts. Around 2006, we were wondering whether we should have a smaller athletic stadium after the Games, or if something larger could be built for eventual use by Premier League Soccer, which would attract more visitors.

Initially the plan was to develop 80,000 seats for the Games and then this would be reduced to 25,000 seats which could be used for athletics and lower league clubs. However, when the new legacy chief arrived she disagreed with having a 25,000-seat stadium that would only be used twice a year for athletics and maybe a few other events, as it would create a dead zone in the middle of the Olympic Park. She pushed for hosting a soccer club that could attract use year-round.

So, a search was made for a soccer club to take it on, however this effort was stopped by a legal challenge because under European competition law you can't give a public asset to a private enterprise for below market value as this is considered an unfair state subsidy. So, we undertook a second bidding process, this time looking for tenants who would occupy it but allow the Legacy Corporation to retain ownership with GLA. The eventual successful bid was West Ham United and UK Athletics.

While the stadium has been very successful as a venue, hosting the 2015 Rugby World Cup, and the 2017 World Athletics and Para Athletics Championships, the cost of conversion was extremely large. Also as we put services like catering, toilet facilities, and hospitality in tents on the outside, these services had to be fitted back into the stadium. Retractable seating was added so that during soccer season seats could be moved closer to the field of play. A roof also had to be installed due to the unreliability of weather in England. So, although the stadium has been a great success, it took a long time and slightly circuitous route to get there – and money would have been saved if these facilities had been built in from the beginning.

Another problematic legacy venue is the former press and broadcast center. Essentially a large shed filled with high quality IT connectivity, but only used for TV studios during the games. There were deliberations on whether to demolish the structure. Fortunately, a deal was eventually made with a joint venture of Delancey and Infinity SDC to convert it into a new type of campus on the edge of Hackney Wick – a former industrial area that's full of artists and creatives.

Now ‘Here East’ is an incredible campus that holds about 5000 jobs, including BT Sports (TV station), two universities who have moved campuses in there, Plexal who are a global innovation center, and Ford Motor Company who are using it to trial autonomous vehicles. It's become a real centerpiece for creativity with a rich mix of different small enterprises and workshops.

Finally, the park itself is very well designed space with two contrasting characters. The South Park is a large, busy civic space – with football fans coming through every other Saturday. The north park is more natural, with a sinuous riverine landscape.

Our challenge was always how to attract visitors to a park that for a long time had suffered from low visitor numbers, but already it is attracting large crowds. The park itself was named Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park to celebrate obviously its Olympic heritage, but also the Queen’s 60th anniversary on the throne in 2012. Two major brands merged together in the name of Queen Elizabeth and the Olympics!

The ‘Legacy Masterplan Framework’ eventually got planning permission in 2012 just in time for the games, and proposed five new neighborhoods. There were a few changes by 2012 though, one of which was that Boris Johnson and the new manager of LLDC expressed the opinion that large-scale blocks with high-density housing weren’t quite the pattern that London wanted.

One of the problems in this part of East London is that when residents do well and start having families they tend to move out because the area lacks family homes and services. A key component we wanted to provide were homes that would keep residents in this part of London.

Mayor Boris Johnson also felt that simply building some housing in the area wasn’t quite ambitious enough. Instead the goal should be to create something akin to a civic contribution to London. So, he started looking back at some of the historic precedents, one being the Great Exhibition in 1851. Starting with the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Kensington area gradually transformed itself into an educational and cultural center. Another precedent is the Festival of Britain in 1951, which celebrated the modernism of post-war optimism. We retained the Royal Festival Hall and built a whole new Cultural District on the south bank of the Thames.

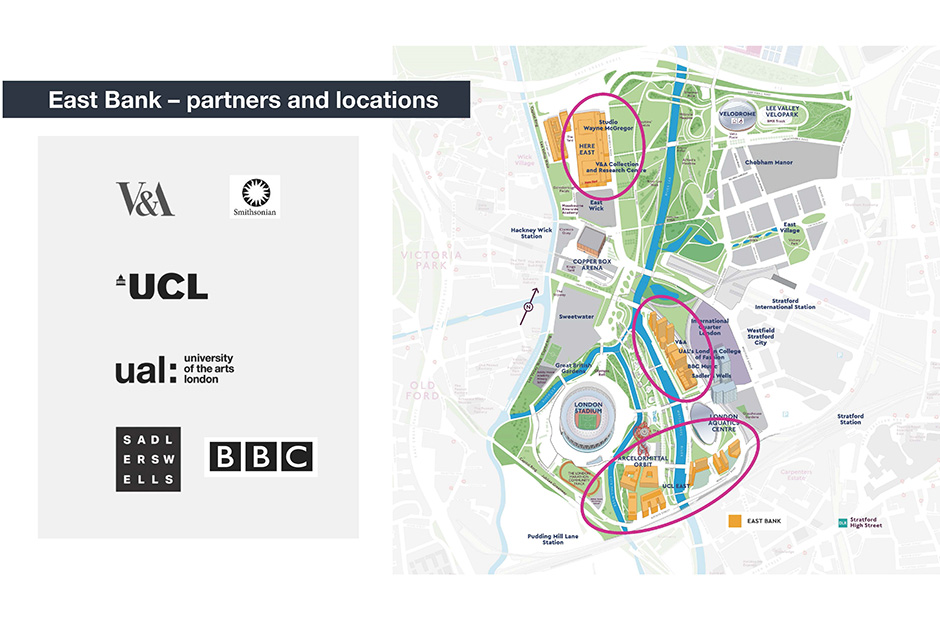

The question was what could we do in East London that would be equivalent. One symbol of the success of the London 2012 Games was that we got partners like the V&A Museum, UCL, the University of the Arts, London College of Fashion, BBC and Sadler's Wells to join. This idea of a whole new culture and zone for education and performance and engineering on the edge of the Olympic Park was being formed on the east bank of the River Lea, creating a new hub.

Specifically, this can be seen in several parts. In the north (at Here East) there is Wayne McGregor's dance studio and rehearsal space and also the V&A's collection space. To the south you have UCL East, a whole new campus in East London for University College London. The most prominent site at Stratford Waterfont, is this network of performance spaces from Sadler's Wells, BBC Music, the V&A and the University of the Art London, and London College of Fashion.

image from : London Legacy Development Corporation

That's the current status of the Olympic Park. Its usage is increasing and these critical masses of new businesses are moving into the areas around it.

In terms of broader legacy commitments, the government made 5 when the bid was launched for the games. We would make the UK the world's leading sporting nation. We would transform East London for the benefit of the people who live there. We would inspire a generation of young people to take part and volunteer more. We would make the Olympic Park a blueprint for sustainable living. And we would showcase the UK, that it was a good place to live, to work and do business and that it was creative, inclusive and welcoming.

In terms of increasing sports participation, the results have been mixed. Like many other countries, the UK is dealing with the problems of obesity and other lifestyle related diseases, and there wasn’t a large change in terms of community sports participation.

In terms of the impact around East London, property prices around the Olympic Park have increased dramatically from their starting point, particularly after 2012. While they went up across London by about three times, they went up in many areas around the Olympic Park by about five times. This shows the area is popular but has led to some levels of displacement of existing communities as affordability becomes a challenge.

At the same time the Games set out to achieve a convergence, or balance, between these historically poorer areas of London and the more affluent neighborhoods. Results so far show East London prospering and improving relative to the rest of the city.

In terms of inspiring young people, the evidence is not conclusive. Many youth expressed excitement for the games, and engagement with the event was fantastic. Nearly a quarter of the games volunteers were 16 to 24-year-olds, galvanizing people across the country.

In terms of the park's sustainability, very little waste was taken to land fill during the construction process, as most was reused, or cleaned up on site. The park is efficient in terms of water management, as it's designed to withstand flooding and to recycle and reclaim rainwater for use in toilets, or in irrigation systems across the park. Also a significant reduction in CO2 emissions was achieved compared to normal building standards, and the park features a very biodiverse habitat filled with native species. Public transport accessibility levels are high and provision is already available for electric vehicles, which will obviously be rapidly adopted in London.

Speaking finally again of legacy, one lasting impact was the opening ceremony which presented to the world and to the UK a very different image of Britain—talking about its rural traditions, its urban culture, the Industrial Revolution, the invention of NHS, the creation of the Internet, some of the things that modern Britain can really be proud of and I think it did a lot to inspire people in the UK.

Live Interview to Richard

Kazuya Yamazaki

How do you assess the current implemented legacy plan, given your experience and role as head of a project team?

Richard Brown

I think it has gone pretty well so far, though it would have been preferable had the government taken the decision back in 2006 to fund stadium conversion to a football stadium from the onset. It would have been a controversial choice because the press would have questioned the decision to build a soccer stadium before securing a tenant, but I believe it would have saved a lot of money and quite a lot of time in the long run.

Overall, though, we have a really successful piece of landscape, some well-operated venues, and a rapidly developing East Bank. The challenge is still a long-term one of financial sustainability, and ensuring that operating costs can be recouped every year, which is particularly difficult when considering the ArcelorMittal Orbit in terms of its ability to generate revenue.

Kazuya Yamazaki

What do you think about the change from a residential area to a cultural education hub?

Richard Brown

It's wonderful in every way (apart from a traditional commercial point-of-view), but a new sort of commercial and civic hub is emerging for the Olympic Park, which is definitely positive.

Actually having things to visit would draw people to the area. One of the visions I always had was that if a tourist were to visit London for a few days, the Olympic Park would be one full-day excursion that most would want to undertake due to the variety of attractions, such as exhibitions, concerts, festivals, or even including a simple picnic on the lawn.

Kazuya Yamazaki

What do we need to create a strong clear vision of big projects such as the Olympic Games and its legacy?

Richard Brown

The bid teams performed exceptionally well, with staff who knew the IOC negotiation process, and a city government that did not interfere heavily. We were all targeting a clear commitment to regeneration and change and to providing the best possible experience for athletes.

One facet that London did differently was to offer this vision of actually transforming this whole area of the city. The immense support from the Mayor of London for this vision of transforming East London was also what helped win the vote in the end.

Kazuya Yamazaki

What’s more important for implementing big projects such as the Olympic Legacy, a powerful leader or sharp followers?

Richard Brown

The interesting thing about the political leadership is it worked seamlessly between the political parties. Both Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson recruited the right people for specific jobs and let them carry out their duties, with little micromanaging from a political level.

For example, in establishing the Olympic Delivery Authority they recruited David Higgins who had built the Athletes Village in the Sydney Olympics, and allowed him significant freedom. As he was an expert construction manager, he performed a large-scale budget review early-on which showed that funding needed to be boosted from around 3 billion pounds to around 9 billion pounds. Overall, they allowed skilled managers without large egos to carry out the roles they were assigned, which benefited delivery of the Games.

Another point that helped was the good political chemistry between Ken Livingstone and Tessa Jowell who is the sports minister. They had connections that went back 20-30 years in London local government politics. But more importantly, they were professional leaders who were performing at a high level. Similarly in the Olympic Delivery Authority we were public sector workers, and so we didn't try to micromanage all the contractors or all the procurement.

Essentially, we didn’t draw the master plans ourselves, nor construct the buildings ourselves. We brought in professional organizations who were the best in their fields to accomplish the task.

It's more important to find a set of principles and a set of objectives that you're aligning everyone around rather than to have or powerful people disagreeing with each other, because we've seen that occur in Olympic cities and it rarely has a positive result.

Kazuya Yamazaki

Why do we need cross-sectional teambuilding in large organizations such as the London Organizing Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (LOCOG).

Richard Brown

One decision we took was to put the Olympic Delivery Authority and the LOCOG in the same building together, which is very important because in Sydney they hadn't done that.

In Sydney they had endless arguments between SOCOG and the Olympic Coordination Authorities (who were performing much of the same job as ODA looking after infrastructure and venues), and eventually they put them in the same building. That was only 2 years out from the games but by that stage everyone was locked in their adversarial positions.

In London’s case, the Olympic Delivery Authority was built up in 2007–2008 and then our numbers started going down because the planning, design, and procurement work had been completed. From that point, most of the work moved on-site.

Kazuya Yamazaki

How did you negotiate with Zaha Hadid to reduce the size of aquatic center?

Richard Brown

It was Dame Alison Nimmo, then the director of design and regeneration and now running the Crown Estate, who dealt with negotiation. The primary challenge which was not entirely her fault was that the river wall had to be able to support the weight of the roof as the site was located adjacent to the river.

The weight of the roof was significant and if the load was only distributed on three pillars, the risk was it would break the river wall, leaving the building unsupported. So there was a lot of work had to be done, just to build up the river wall to support the weight of the building.

In fact, the aquatic center was going to be built even if we didn't win the Olympics. It was planned for development regardless and in fact it was part of us showing the IOC we were serious about sports centers.

Kazuya Yamazaki

Let us shift our focus from the Olympic Park to King’s Cross Station, which I believe is another good example of redevelopment. What do you think about King's Cross in terms of possible take-aways that could be applied to the Olympic Park area?

Richard Brown

We learnt quite a lot from King's Cross and the people from Argent who are the developers. One big take-away was the inclusion of the University of Arts London (UAL). UAL is a big institution that incorporates numerous different colleges. The one coming to the Olympic Park is London College of Fashion, at King's Cross they've got Central St. Martin's which is the primary fine arts school. We noticed that and considering the east bank and the value of getting the university tenant in early, we believed strongly that it would bring life to the area.

The other thing we learned from them was their approach to development, which is rather than selling off different blocks of land, they act as master developer. They get the planning permission then they enter into joint ventures for different sites with different partners, and that's the approach being taken for the different phases of legacy development. Rather than selling off land and losing control, we retain it and the long-term benefit.

Q&A Session

Question 1

The Olympics are notorious for gentrification. Was there any initiative to include overlooked populations and retain the existing history/arts/culture of the area?

Richard Brown

It is a challenge we've had in East London. We did a lot to try and ensure that local people around the park were able to access jobs, and opportunities in the park. There are high levels of local employment in all the legacy uses. You mentioned overlooked population, and I think one of the things that has been most successful is having residents from the local Bangladeshi Community, particularly young women, to work as construction apprentices which was a big achievement.

I've always felt that after the Olympics there should be a process of slow reabsorption of the Olympic Park into East London. And I'd like in 10 years’ time for the Olympic Park to blend in and become part of the urban fabric of East London, to the point where you might walk through it and not realize you had entered the Park proper.

Some people have been priced out of areas like Hackney Wick, where a very rich culture and a huge concentration of artists have retained their characters, but a lot of original residents remain. It is still a significant worry though, and rather than gentrification, I would hope to see current residents becoming more wealthy and being able to access opportunities in the park.

Kazuya Yamazaki

Would you elaborate on the development of Here East as well?

Richard Brown

I think Here East really tries to draw on various characteristics from the area. It's very odd, on one side of the Olympic Park there’s Hackney Wick with all these funky stylish artist studios, craft beer breweries, and on the other side you got this huge corporate shopping mall from Westfield. So these two very different characters on either side and I'd like to think that the Olympic Park is this place for convergence, that has an aspect of commercialism but doesn't lose a sort of rough edge creativity.

Another example is Sadler's Wells moving in. Sadler's Wells is a classical ballet dance company, who very specifically wanted to open up a theater in East London focused on street dance, hip-hop, doing things that are more connected with the local community rather than people on their toe tips in the more traditional ballet style.

Question 2

London 2012 was advertised to be for everyone; however, low-income population often suffer from worsened conditions. How did London deal with this concern?

Richard Brown

The impact of the Olympics in some cities has involved the displacement of whole communities. In London, though, very few people were displaced.

Tessa Jowell, the Minister for the Olympics, was also very focused on making sure that tickets were priced to be accessible. She also made them available for local schools at cut rates, and offered Park tickets so you could just come in and visit the park. So, while top-rated tickets were very expensive we were very keen that the venue should be full and that people should feel that it had all the diversity of London in those venues.

The other worry was related to landlords who in the run up to the Games were trying to get people evicted from their accommodation, so that they could rent rooms out for the Olympics. This activity was quite hard to stop based on current legislation, but in the end most landlords did not end up making the vast sums they had envisioned due to people being unwilling to pay high prices and due to the abundant supply of hotel rooms.

Overall it was an event that was enjoyed by Londoners at all income levels, and there was a sense of being open to everyone. We still hoped that it would have a positive impact in East London as well, though.

Kazuya Yamazaki

So in that sense, as part of a housing development, are there many affordable housing options?

Richard Brown

This special housing is not exceptionally cheap, but there is a new tenure in London called London Living Rent, which is baselined on the median local income in the area.

Under Sadiq Khan affordable housing has been a real priority since he became mayor, so the affordable housing numbers have been pushed up, which will be having an impact—with I believe the target being 50% of new housing being affordable.

Question 3:Kazuya Yamazaki

How did the Olympic development change the perception of the waterfront? Do you think these kinds of changes are possible on the Tokyo waterfront?

Richard Brown

The site is slightly removed from the riverfront, but it did change the image of that part of London. It made people realize how close this area was, as well as its value, leading people to discover new interests in the neighborhood. It’s helping to create a sort of sub-center for London and Stratford.

In terms of Tokyo, there are some very beautiful sports venues being built. It will depend on how the uses will be split between being a sports zone, or an industrial and commercial complex, or living, and seeing that plan come together.

Question 4:Kazuya Yamazaki

In comparison with London where redevelopment was the goal, Tokyo is aiming to reuse existing sites. In Tokyo, though, we haven’t been hearing anything about societal or community-driven legacy plans, perhaps due to the lack of new infrastructure being built. Consequently, I feel that there has yet to be an atmosphere of welcoming the Olympics from the public. Is there anything that Tokyo should do or decide upon from here on out?

Richard Brown

I think, one thing that's really exciting about the Tokyo Games is that it's the first Olympics that I can think of that's reused previous Olympic venues, for example reusing the Yoyogi National Stadium which is such a fantastic iconic building.

We can talk about sustainability in the context of London, but in general new buildings are not particularly sustainable. If you reuse old buildings that's always going to be the more sustainable option, so I think that mixture of reusing the venues some of those venues in Central Tokyo as well as building some new venues on the waterfront seems very positive.

In terms of legacy, we in London didn't set up the legacy development corporation until 2010 and it was planned in 2012 and formally established. With the Games almost here, it will soon be too late to think about legacy structures. There's of course still an opportunity before the games, and I’m sure it’s an area that TMG is already planning—especially so because they are building most of the new permanent venues.

Closing

Prof. Hiroo Ichikawa

To begin it seems that London was successful in its aim to improve the lives of disadvantaged residents in East London’s Stratford and promote social inclusion.

It was clear from today’s talk that through Stratford’s development and the completion of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, the area was changed, which in effect has changed London as well. This could rightly be defined as the legacy.

Concerning the connection between London and Tokyo, during the 1980s when East London was being developed, so too was Tokyo’s bayfront area. Following that, although the International Urban Expo was cancelled in 1995 and large-scale change in the city failed to take place, Tokyo now once again has the opportunity to take the limelight with the 2020 Games.

Not only acting as a venue for sports festivals, I believe that the waterfront will from here on act as a pivotal point in urban development, influencing Tokyo further.