Executive Director, The Mori Memorial Foundation

Tokyo: Urban Identity in Globalization

Roppongi Academyhills Towerhall

Executive Director, The Mori Memorial Foundation

Introduction: What is the Identity of a City?

Ichikawa

The topic of the first urban development session is Tokyo’s identity. Does it have one? If so, what is it?

A quick look at the major cities of the world shows that in this day and age, all of them are characterized by having a cityscape dominated by skyscrapers. Bangkok, Manila, Beijing, and Seoul are just some examples of cities where high-rise buildings are starting to cover their urban centers. In cities like Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur, the construction of iconic towers helps set them apart from other cities. In Hong Kong, a city renowned for its many skyscrapers, the skyline continues to climb higher with the construction of the International Finance Centre and the International Commerce Centre, both of which are taller than 400 meters. Tokyo too is no exception to this trend with many new high-rises scheduled for construction over the next 10 years.

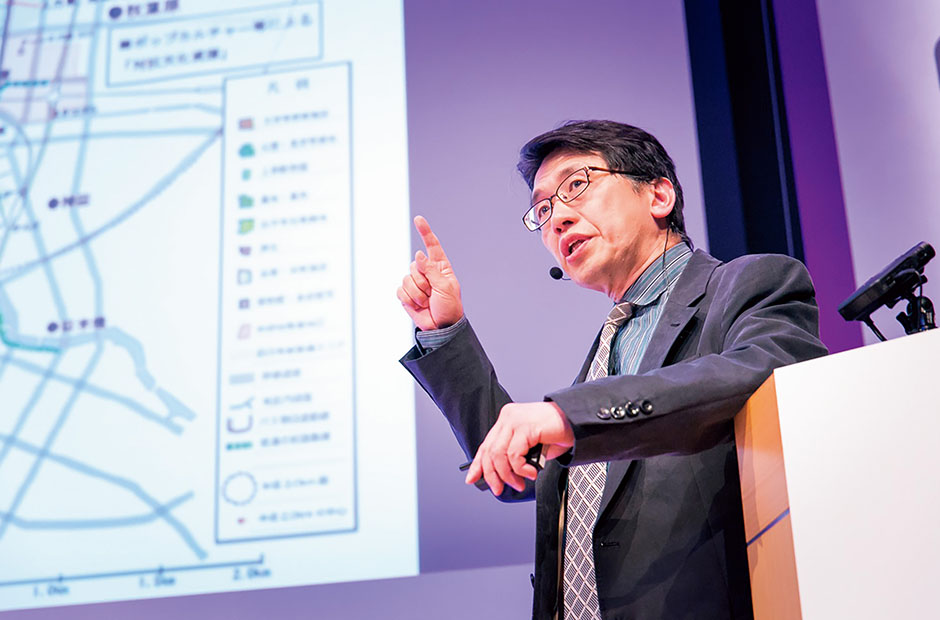

Urban development of Tokyo’s inner city areas

Firstly, the Otemachi, Marunouchi, and Yurakucho areas will continue to see more tall buildings built in the next 10 years. In Otemachi, buildings are being successively replaced with new ones during each phase of a so-called “chain redevelopment project.” A high-rise building about 390 meters in height is also slated for construction in Tokiwabashi north of Tokyo Station close to the Nihonbashi and Yaesu precincts. Meanwhile, in Toranomon, two new skyscrapers are set to go up on both sides of Toranomon Hills, which was only just completed in 2014. In Shibuya, a large-scale redevelopment project continues, including the transformation of Shibuya Station.

These are just some examples of the ongoing development at different locations around Tokyo and the growing trend for the construction of inner-city high-rises, while a similar phenomenon can also be observed in other global cities. In this environment, we need to thoroughly discuss how Tokyo should promote its urban characteristics and determine what the city’s identity really is. Urban Development Session 1 welcomes Professor Sharon Zukin and Mr. David Malott from New York, and Professor Shunya Yoshimi from Tokyo to hear their thoughts on Tokyo’s identity from the perspectives of sociology and architecture.

Complexity and Contradiction in the “Authentic” City

Zukin

What is authenticity?

The term authenticity has been used especially in marketing since the early 2000s to express a real essence of products as well as cities. I chose to use this term to try to grasp the sense of loss in a city with current redevelopment strategies. However, the term has contradictory meanings. On one hand, authenticity means that a culture is very old. On the other hand, it also refers to products of culture that are brilliantly new and never seen before. Second, a meaning of authenticity that goes back in time is that authentic things are products of a group culture. On the other hand, we often speak of the work of an individual genius as authentic. Finally, when an art expert uses the term authenticity, they mean something that can be certified on the basis of objective standards. But when we speak in everyday language of authenticity, we speak about the way we feel, the subjective feelings that cannot be certified. These contradictions cannot be resolved and are part of the word authenticity.

One thing that may disturb us as analysts and as planners is that the view of the city from inside is different from the view from outside. If you are looking from outside, it is easy to use the word authenticity because you have a critical distance. But if you are living inside an authentic city, you don’t think of using the word authenticity because that is your life. When you walk through a neighborhood or a district of the city, you may see the same things everywhere—for example, you may see residents sitting outside on the sidewalk. Do you call that landscape distinctive and authentic, or do you just think it is normal?

In New York, I am most impressed by the foundation of a living authenticity in material production, everyday routines, and the sustaining of edges between different cultures. I think that these three conditions are important for us to fight against standardization. However, what we see around the world instead is that the competition between cities for capital investment, for tourists, and for reputation creates a standardized set of redevelopment practices. I would call our attention to the standardization of the development strategies that all come out of one “global toolkit,” where people meet, talk, and use the same kinds of ideas in different places. Those examples are not only seen in mixed-use high-rise developments, and waterfront developments, but also in the global diffusion of cultural symbols and the mega-events of the world stage. I am sorry to say that the modern Olympics have become one of those standardized mega-events.

The global toolkit of redevelopment strategies is not only based on the soft power of images and taste, but also on the relatively hard power of rankings and branding mechanisms. This results in an intensified competition between cities, and everyone looks to the “highest-ranking” cities to form their ideas about the way their own city should look. This creates too much standardization, an unhealthy loss of authenticity.

Authenticity of Tokyo

Let me speak a little bit about what I have seen that looks authentic to me in Tokyo, even though I am an outsider. I look at the form of the buildings, who uses the buildings and what the uses of the buildings are. And I look to see a continuity between past and future. For me it is very important to preserve Tokyo’s remaining, historic low scale. In Shimokitazawa, the old black market from after World War II has been demolished for redevelopment, and in Kagurazaka, the streetscape looks like many small streetscapes at night, with restaurant signs and fairly low-rise houses. Local shopping streets, even though they face extreme competition from big stores, chains, and online retail shopping, are important for protecting a sense of local identity. It is these shops and the personal presence of the owners and workers in the shops that create a very strong sense of local identity and continuity. Low scale is also human scale.

As we build new parts of cities, we should preserve the space for face-to-face relations. In Tokyo, we often find small shops with a Coca-Cola vending machine on its side. This indicates that local culture is never completely closed to the outside. My Tokyo research partners, who collaborated with me on my new book, called Global Cities, Local Streets, developed the term “globalized authenticity,” precisely to express the sense that in Tokyo the local is always global. We know that everywhere the global must come to rest in the built environment, so that the global always becomes local. However, Tokyo’s gift to urbanists around the world is to make this globalized sense of local authenticity. That is what should continue, but strongly grounded in material production, edges between cultures, and the sustaining of the juxtaposition between the old and the new, the low and the high.

Creating Identity in the Global Context

Malott

In dealing with globalization in architecture, we face the problem that cities around the world are beginning to look like each other. Today, we are able to get material from around the world. Architects and developers are able to practice and build around the world. So, how does one maintain uniqueness in this age of globalization? I would like to show briefly four projects which I had a hand in: the Shanghai World Financial Center (SWFC), a landmark tower for Dubai, a new residential tower in Mumbai, and finally, a futuristic city in Tokyo.

Shanghai World Financial Center, Shanghai

When KPF started the design for the SWFC, it was a question of how to design a building that responds to its name – it is a world financial center – while at the same time creates some aspect of place. There is a kind of Asian-ness to the building which grows out of its Zen-like simplicity. The author of the design, my mentor William Pedersen, describes the form as the intersection of two elemental geometries: the square, representing the earth, and the circle, representing the sky. If you think of the skyscraper as a bridge between the earth and the sky, it is a very poetic way of explaining the design. While much has been said about how towers meet the ground to create streets and public spaces, what makes this tower very special is also how it meets the sky. This is where we bring the low city to the high city. It lifts the public experience to the very top of the building. The tower resolves itself into a sky bridge ― a sky street at the very top of the aperture. What we have done is to take a skyscraper, which is traditionally very closed, cold, and solid, and begin to carve it out and open it up.

Dubai

There is an issue that some parts of the tall building are related to “density”. Density is needed for our cities to grow, but in tall buildings we also find an element of “vanity”. If you look at the peacock, for example, the body of the bird is actually small. The rest of it is feathers – that is the vain part. At the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), we actually measure the vanity of buildings by looking at how much of the building is usable and how much is the peacock’s feathers. It turned out that the place with the most vanity height is Dubai. In such a context, we proposed a design for the world’s tallest commercial building where, as with SWFC, we elevated the human experience to the highest point of the tower in the form a horizontal sky ring gesturing out over the city. This building was trying to create a bottom-up building in a very top-down society. It is a design which you can see very much grows out of where it is, but aspires to what the place should become.

Mumbai

India is a fascinating place where symbolism is deeply important and nature is held sacred. When we approached the design of a new landmark tower in Mumbai, we asked how we find something that responds to the place-that responds to this love of nature. I think, in a way, one aspires to what the city can become, so rather than creating a closed tower, we developed an idea to open up the tower and allow it to breathe. This is quite unusual for upscale residential towers in India, where typically the residents walk off their elevator directly into the unit without interacting with their neighbors. We proposed to make a communal space in the center of the plan, where light and air can enter. Even though you are living in a high-rise, you can feel the presence of nature at the very heart of the building.

Next Tokyo

In Tokyo, we were approached to do a tall tower built on the infrastructure of the Aqua-Line which connects the two sides of Tokyo Bay. We called it “Next Tokyo,” a future city which also functions as a resilient barrier spanning across the bay. If there ever was to be a tsunami wave that came into Tokyo Bay, this would be a breakwater, a dam to slow the tsunami. The idea also came from discussions with the late Mr. Minoru Mori about the compact city. We shared a belief that tall buildings exist not for the sake of height, but to enable our sustainable future. Urban sprawl is happening in Tokyo, and in many parts of the world, nowhere worse than in Los Angeles, where so much of the land is turned over to transportation. If you consider the waste of material, the waste of energy, the waste of time-energy in commuting, you can understand why Mr. Mori believed in the compact city. It is the idea of compacting our city so we can live in it, and increasing vertical density to free up space for nature. Next Tokyo expands upon that idea by building up on infrastructure. I call it the compact and connected city.

Next Tokyo sits in the bay and, as its infrastructure spans across the bay, it creates the potential for new land. The ringed structures in the bay act as resilient barriers which support buildings above and, over time, can change the ecology of the bay. As with a volcanic atoll, the ring begins to support life—fresh water, agriculture, society, and culture. So the project does acquire a certain Japanese-ness, in that the mechanism of forming new land is symbolic of Japan’s very formation as an island made from volcanos. Next Tokyo is not literally looking Japanese but it embraces the essence of the Japanese character.

When we think about the idea of the tall building and its DNA, the role of architecture is simply to support the life that is contained within. What I am really advocating is to take our tall buildings and make them more porous, to open them up to nature and to society. Ultimately, what is it that creates uniqueness? My answer is, all of us. It is people who bring the unique identity to a place.

Central Tokyo North and Creative Recycling of City

Yoshimi

Vision for a Tokyo Cultural Resources District

The concept of a Tokyo Cultural Resources District is one that aims to create a new area in the north of Tokyo’s urban center to uncover the concentration of cultural resources found within a two-kilometer radius that encompasses Akihabara, Jinbocho, Kanda, Yushima, Hongo, Ueno, Yanaka, Nezu, and Sendagi. Cultural resources in this district include the traditional lifestyles of Yanaka, Nezu, and Sendagi, the galleries, museums, and artistic culture found in Ueno, the academic culture ascribed to Tokyo University in Hongo, the Yushima Seido “sacred hall” and Yushima Tenjin Shinto shrine in Yushima, the bookstores of Jinbocho, and the pop culture of anime and manga associated with Akihabara. It is a little-known fact that all of these areas are part of the same district.

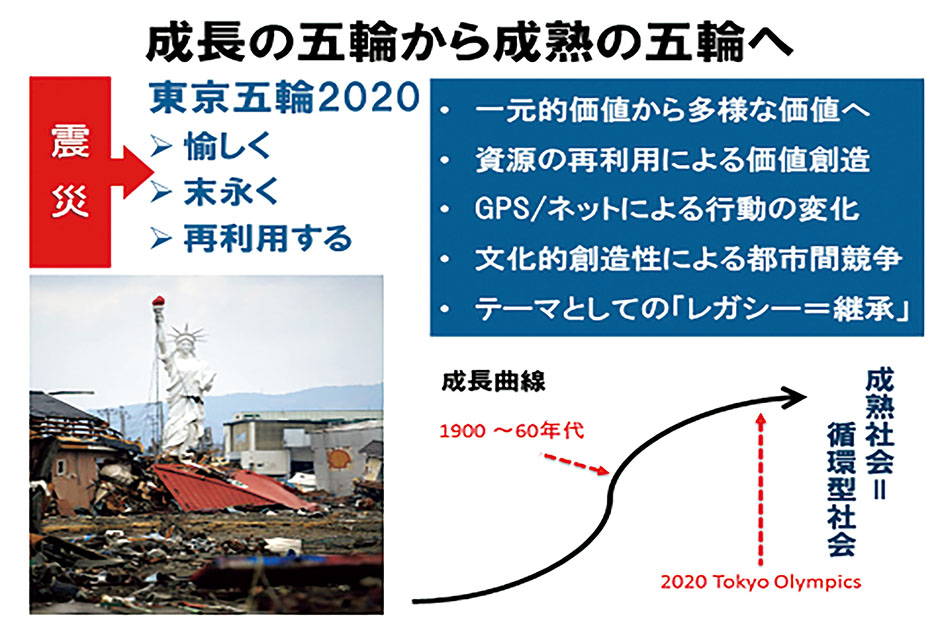

Challenges ahead of 2020 Tokyo Olympics

Despite Tokyo currently gearing up for the Olympic Games in 2020, unlike London in 2012, it has yet to draw up a concrete vision for the event. This is because the city has not yet cast aside the values it embraced during the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Those games were held during a time of high economic growth and therefore focused on the core theme of rapid and vigorous urban development. But Tokyo in the year 2020 will represent a mature society rather than one that is still growing. The values we must espouse this time around should include the notions of enjoyment, longevity, and recycling, instead of rapid and robust growth. To this end, we must turn our attention to values of diversity, not uniformity, which will hinge on how Tokyo expresses its identity as a city that creates value through the process of recycling.

The culture of Tokyo’s northern district

With the hosting of the Olympic Games in 1964, Tokyo’s urban center shifted from north to south, which meant that the north, where most of its cultural facilities were located at that time, was largely ignored. So how can we reclaim the culture found in Tokyo’s northern district? Some ideas I have include a competition on renovating old buildings in Kanda and Yushima, establishing a school for social projects to develop human resources and utilize cultural resources, and the hosting of a Tokyo biennale in 2020 in this very district. Moreover, the University of Tokyo, Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Gakushuin University, and many private universities were established in Jinbocho and Kanda, subsequently giving rise to the emergence of Japan’s academic culture in this part of Tokyo. In this area where many universities are still located, I would like to see them come together to create a framework through which they can make practical contributions to the community. The framework that I envisage for urban development first involves the planning of a definitive project, or the so-called “software”, before developing the “hardware” needed to ensure the project comes to fruition.

I think it is important that we once again unearth the culture of northern Tokyo, which once formed the city’s center during the Edo period, and show to the world how impressive Tokyo’s culture is. If we can uncover the wealth of cultural resources that await us there, I think we can incorporate the north of Tokyo into a much larger framework that embodies the city’s identity.

Panel Discussion

Ichikawa

Spatial Diversity in Tokyo ― Hiroo Ichikawa

In responding to the question regarding Tokyo’s identity, I would like to say that the city can be described as having a diversity of areas that have developed over a very long time. For example, Marunouchi, Asakusa, Ginza, Nihonbashi, Odaiba, Shinagawa, Roppongi, Shibuya, and Shinjuku. All of these areas are urban centers in their own right. No other city can lay claim to having so many centers as Tokyo. Tokyo’s diversity of areas is due to the fact it boasts the world’s largest metropolitan area population of 37 million people. As such, Tokyo’s communities have developed through the buildup of activities of so many people over the course of time.

For example, the area of Marunouchi was a showcase of the city’s modernization and transformation from Edo into Tokyo during the Meiji period. The area was even known as “London Street” after its development was modeled on Lombard Street in London and continues to serve as Tokyo’s central business district today. In addition, Nihonbashi functioned as Japan’s financial center in the Edo period; the gold mint was located there alongside rows of merchant houses. Roppongi used to be home to a large number of military facilities. Before World War II, the Imperial Japanese Army maintained some barracks in the area, but then after the war, it transformed into a district mainly occupied by the US military, giving rise to many stores, bars, and restaurants catering to foreign people. With the opening of the Yamanote Line in the Meiji era, Shibuya developed into an important railway junction, and is now a center of youth culture.

So, Tokyo boasts a diversity of areas, but what does the future hold for Japan’s capital city? How do we incorporate Tokyo’s identity into future urban development projects? It is these points that we would like to focus on as part of our discussion today.

Ichikawa

Diversity is a topic currently being debated in many places around the world with various interpretations of what it actually means. In terms of racial and ethnic diversity, Tokyo is probably ranked the worst of all global cities due to its homogenous society. I would like to hear your thoughts and opinions about Tokyo’s spatial diversity.

Malott

Tokyo has a wonderful juxtaposition of scale, not only in size but also in time. We can get something big like Roppongi Hills literally next door to a noodle shop or an old shrine, and that’s what makes Tokyo fascinating. Tokyo is also a wonderful paradox where there is order when there should be chaos. Tokyo has a distinctive randomness in its roads, and yet traffic is manageable.

I’ve been coming to Tokyo many times, but each time I feel like the city becoming more and more interesting and is taking steps towards becoming more global. However, I think Japan face the fundamental choices of, do we want to remain a global power by dealing with the population decrease, or do we want to go the way of Switzerland ― a place that has a very high quality life but not at the forefront of global innovation or power.

Yoshimi

Hearing the word “diversity” made me think of the children’s storybook called “Swimmy.” The story follows a small fish named Swimmy who wards off bigger fish by teaming up and swimming with many of his own kind to give the appearance that he is much bigger than he really is. Tokyo’s diversity somewhat resembles this scenario.

Tokyo is a city teeming with spatial diversity. No other city comes close to Tokyo in terms of the number of small art galleries, museums, and restaurants that can be found in its inner-city areas. And much like the story of Swimmy, the city has the potential to become a bigger city by linking smaller and sophisticated parts. On the other hand, from the perspective of social, linguistic, and cultural diversity, Tokyo ranks very poorly compared with global cities like London and New York. So, the question of how Tokyo can extend its abundant spatial diversity to social diversity is a key issue that probably needs discussing when we consider the city’s future development.

Zukin

When you speak about digging deep, that certainly expresses the idea that cities are built in layers. Sometimes the outsiders cannot see the older layers because they have been covered over. But the layers exist and shape to some degree what comes. We have the vertical growth of the city, in both a historical and a metaphorical sense. On the other hand we also have increasing functions of cities. So there are more groups of people coming to cities with some concentrations of activities weakening, and new concentrations growing. That is a horizontal growth of cities. Diversity is a logical result of both the vertical and horizontal growth of cities. In these times, ethnic diversity is increasingly important. In that sense, paradoxically, diversity helps to sustain authenticity. Nonetheless, it is difficult for an outsider to make a prescription, to say this is how the city must become more diverse. Perhaps issues that are outside of our range of expertise are important.