Professional Graduate School of Governance Studies, Meiji University /

Executive Director, The Mori Memorial Foundation

The Innovative City Forum 2014, held on October 9, 2014, was an international conference to discuss the theme of “designing the future for global cities and lifestyles,” with a focus on the question of “how will we be living in 20 years?” The urban development session, organized by The Mori Memorial Foundation’s Institute for Urban Strategies, was centered on the visions of global cities over the next ten years. Experts in urbanism and architecture were gathered from London, New York, Paris, and Tokyo to elaborate on the ongoing development projects and policies in their respective cities and engage in a lively discussion on the visions of the global cities in 2025. This section sums up some of the highlights from the session.

The many development projects that are currently underway in London, New York and Paris will largely transform these cities within the next 10 or 15 years. In London, there are large-scale complex developments on the banks of the River Thames in the district of Nine Elms and in the area of Kings Cross, while in the Royal Docks area, major development projects are being planned centering on the London City Airport. In New York too, large-scale redevelopment projects are planned for the Hudson Yards area, the former World Trade Center site, and an old factory site in Williamsburg. In Paris also, the revitalization of the metropolitan region is being shaped by the government’s Métropole du Grand Paris initiative. As its rival cities around the world take steps to transform themselves on a grand scale, we need to consider what kind of future vision we should draw for Tokyo over the next 10 years, leading to 2025.

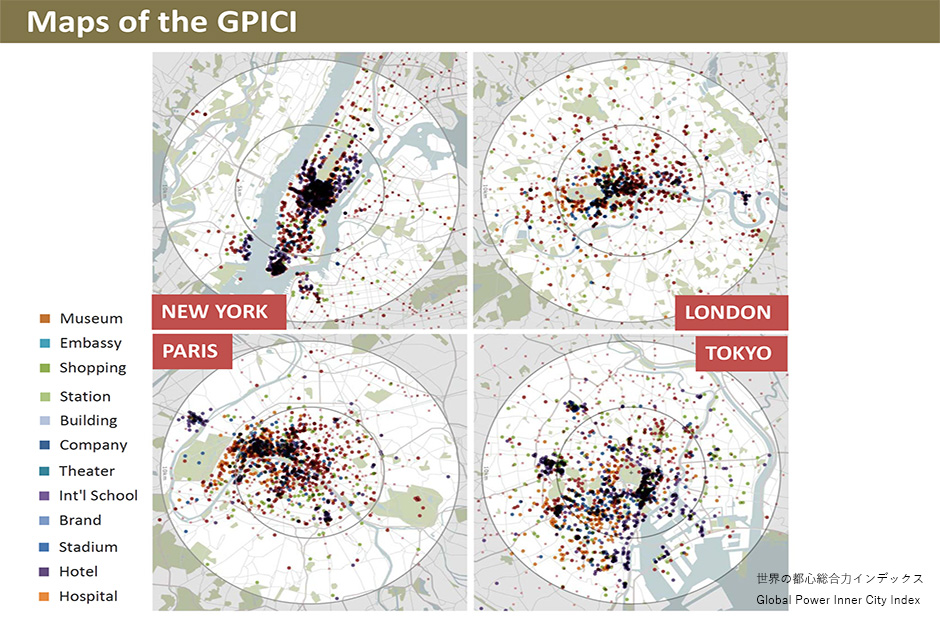

In shaping a vision of the future for Tokyo, we first attempted to analyze Tokyo’s current situation using the three studies carried out by the Institute for Urban Strategies, The Mori Memorial Foundation, namely, the Global Power City Index (GPCI), the Global Power Inner City Index (GPICI), and the Global Power Metropolitan Area Index (GPMAI). The GPCI is a comprehensive ranking of 40 global cities with 70 indicators in six functions (Economy, Research and Development, Cultural Interaction, Livability, Environment, and Accessibility). The GPICI is a comprehensive ranking of city centers, which analyzes and evaluates the urban power of 5km and 10km inner city zones of eight major metropolises around the world from the perspective of six properties (Vital, Cultural, Interactive, Luxury, Amenity, and Mobility). The GPMAI analyzes and evaluates the strengths of the metropolitan area (50km zone from city center) of 10 leading global cities from the viewpoint of five functions (Vitality, Intelligence, Interactivity, Network, and Sustainability) and three dynamisms (Stock, Flow, and Growth).

Key findings of these research are the following: from the perspective of Tokyo’s comprehensive power, although Tokyo has strengths in the functions of Economy and Research and Development, it is relatively weak when compared with the top three cities London, New York and Paris in the function of Cultural Interaction and the indicator group of International Transportation Network within Accessibility. On the other hand, if we take a look at inner city strength, we can see that of all the global cities, Tokyo in particular possesses a very strong ability to accumulate resources in its inner city areas. As for the strength of its metropolitan area, despite being rated highly for the dynamism of Stock, the assessment of Flow and Growth for Tokyo is not quite as high. Urban strategies for Tokyo’s future will need to be formulated in light of these circumstances.

In coming up with new urban strategies for Tokyo, it is important that we first predict how the population structure of Japan and Tokyo will change in the future. It is estimated that by around the year 2035, the number of people aged 65 or more will be double that of Japan’s young population. However, despite Japan’s current total population decreasing, Tokyo’s population is expected to keep increasing up until the year 2025. It is important to note here that approximately 70% of Japan’s population is concentrated along western national axis including the country’s Pacific belt, which span from Tokyo down to Fukuoka, and this ratio is expected to increase to roughly 80% by around the year 2040. The fact that Tokyo is situated at the pivot of this region will naturally determine the functions that Tokyo will be required to fulfill.

As Tokyo evolves over the next 10 to 15 years, the one event that will have the biggest impact on the city will be the Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games to be held in Tokyo in 2020 (collectively, Tokyo Olympics). In preparation for the Tokyo Olympics and thereafter, an increase in the number of arrivals and departures at both Haneda and Narita airports is being examined. Post-Olympics, an increase to as many as 1.10 million is being considered, which will allow Tokyo to rank alongside London and New York. However, to achieve this, not only is a new runway needed, but restrictions on hitherto unauthorized flight paths over the inner city areas of Tokyo also needs to be lifted. In other words, we have to assume that what is not in existence now may become a possibility.

In addition to development related to the Tokyo Olympics, a number of inner city areas of Tokyo will undergo significant change in the future. A series of redevelopment projects is underway in the Otemachi, Marunouchi, and Yurakucho areas, including a plan to revamp the plaza in front of Tokyo Station, while efforts are also being made to change the Nihonbashi district by reviving the Edo streetscape atmosphere of the area. In the areas of Toranomon and Roppongi, there are development projects around Toranomon Hills, which include the construction of a bus terminal and new subway station. Large-scale developments are also ongoing in Shibuya, together with construction work to upgrade the station building. A new station on the JR Yamanote Line is also planned for construction at an existing rail yard in Shinagawa.

Up until now, Tokyo has continued to employ urban policies that focus on a multi-core urban structure. However, areas of the city still continue to be developed in line with the Circular Megalopolis Structure Plan formulated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government in 2001. This means that the future ability of Tokyo to accumulate resources in its inner city areas will grow stronger and largely transform the city in the process. Yet, the picture of Tokyo’s inner city areas that this depicts is not of a city troubled by the congestion of obstacles like in the past, but of an attractive city brimming with nature and the concentration of various functions.

An intensification is probably the one word that sums up the policies guiding London at the moment. London is a global city and it is growing. A decision was made quite a long time ago that London was not going to continue outwards. Therefore, it had to basically recycle land and infrastructure, and get bigger and get denser and become more intense.

In London, the developable lands that have opportunities lie in the east where the old industry and the docklands exist. Thirty years ago, the area was disused derelict dockland. But when moving further east, there are still such kind of condition, like low density, contaminated land and old infrastructure. And the whole reason for bidding for the Olympics for 2012 was to use the Olympics as a catalyst to try and pull investment and interest into the very difficult area of the city to develop.

There were three master plans for the Olympics. The first master plan guided the development of the Olympics as a games venue. Lots of strategy were around being very careful on our design and on the sustainability of our design practices. A second master plan is the transition master plan, which was just completed. The entire park was deliberately closed down for two years while we adapted and dismantled and prepared a long-term development platform. A third master plan tries to tackle this really difficult problem for a city. The Olympic Park was built to secure specialist games campus, but it is not necessary after the games. The Park is required to become an organic piece of city for urban growth to happen.

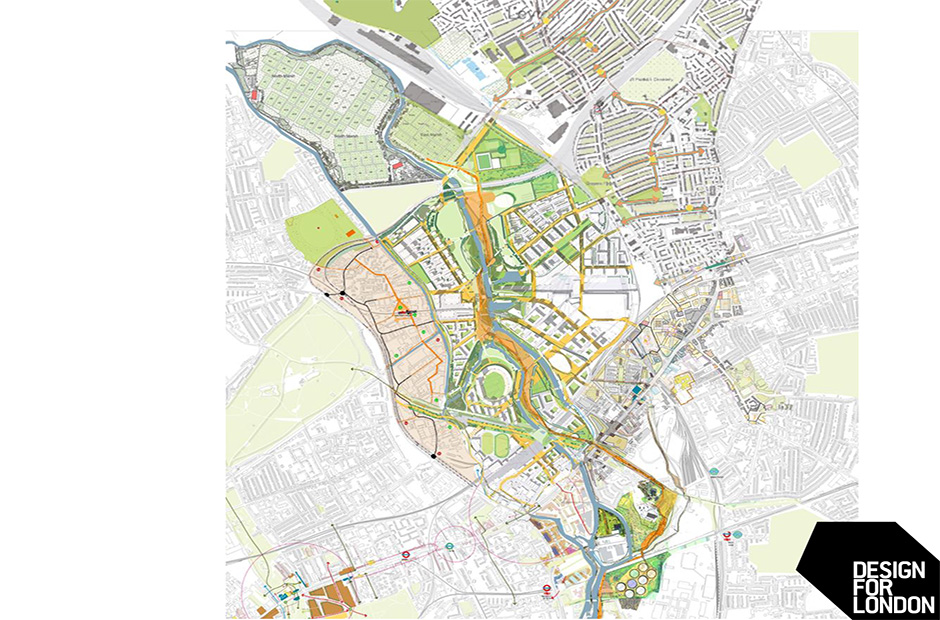

There were six very simple spatial strategies for the Olympic Park. The first was to attain elements of the games as a memory, which could actually form a structure for future planning. The second was to deliberately construct a set of neighborhoods reflecting the settlement patterns of London. The third was to improve connectivity and build a structure of roads and streets. This again was very much on the basis of London’s structure. The fourth was to use open space. The fifth was to use water. The sixth was to aspire to producing a very complex piece of city, which would have built into its planning its ability to adapt and change over time.

King’s Cross set out to become another piece of London. It set out to be of a human scale. Deliberately we studied parts of our city. It was decided that eight, ten, or twelve stories was about the right kind of scale to make a very good and valuable piece of real estate in London. Then, the master plan was produced. The critical thing about the master plan was that between the two railways was to come up with an urban form which reconciled the areas on either side and which also deliberately retained the historic fabric. The master plan was deliberately drawn up to try and make sense of them within a new piece of city.

For a number of years I run Design for London, which was the mayor of London’s architectural studio. We became very interested in small scale interventions. We were interested in how we could do very simple small scale things to try and change areas. We became interested incremental urbanism and temporary urbanism. We become interested in how to take a piece of city apart like a watch and then how to put them back together again and try and make them work better. We became very interested in a methodology where we worked with valuing what’s there, work within what was possible and try to define and do the small things that were missing to put a neighborhood on a different track toward improvement.

One thing I would stress is whatever you do, there has to be room. Cities have to make space for the unexpected. Cities have to make space for people to do things in a way that city planning can never do.

It can be said that cities are really a global salvation and can help us in terms of prosperity, sustainability, and social change. It is found that people, especially in our dense cities today, feel overwhelmed by the complexity of the times in which we live. The world has always been a complex place, but today, because of technology, we have a view into the complexity of the world and the world beyond us in a way that we never have before.

The seven billion of us live in a quite scattered array across the planet. If all seven billion of us lived not at skyscraper density, but actually only about three or four story brownstone density, about 75 units to the hectare, that all seven billion of us could fit in the state of Texas in the United States. It means that how we live in terms of density will dictate the future of the world. If we can live in a more dense way, we will certainly lower our carbon impact and create a better planet. What I found in talking to people about that, is that density or intensification causes a sense of namelessness and facelessness that scares people.

We became lost in that world. I think we have really lost our way in terms of understanding the true beauty. I want to talk about how, in the 21st and 22nd century, beauty could actually, be a way in which people can embrace the complexity of the world. In order to do that we no longer need an architect as a superhero. We need an extraordinary group of skills. We need men, women, and people of all different orientations, races, and skills to try to give us that beauty and give us that lens into the complexity.

We should not live out in the horizontal sprawl and try to use technology, windmills, and solar panels to fix that 20th century model. Instead, we should use our cities to build densely and leave nature natural. We should be able to access nature in a much more direct way which are connected largely by train. At the same time, we understand that the hub and spoke model of our cities is actually changing. The idea that people live outside of our cities and commute into a central business district every day is changing very rapidly. Because of technology we are moving into a network city model. In this model, throughout a big city you can find an archipelago, a series of islands of places where people live, work and play across many districts.

We are really rediscovering the area in that 10 kilometer belt outside of Manhattan. This is part of a new waterfront for Brooklyn, named the Domino project. We tried very carefully to move and interpret the complexity of the city in terms of the lower scale of this neighborhood, the scale of the bridge and the factory and then the scale of the skyline. It is really about building neighborhood. It is critically important how these buildings meet the street in terms of building that neighborhood. We found that 85% of our new technology jobs are in heritage buildings. They are in pre-war buildings because those people do not actually want to be in tall towers. They want to be in a different kind of work environment. So this is something we are very much trying to build in New York. We are also trying to emphasize a new skyline in Brooklyn. Brooklyn is sort of the next chapter in New York’s history.

The Barclays Center is the first arena in the United States that has no parking associated with it. There is not one single car parking space. The building is made of corten steel. This is only possible because of the computer. It is designed on the computer and it goes directly to the metal fabricator. What is important about this kind of city building is that it is part of the city and integrates into the city in terms of new and old as well as high and low. This is something that is very important if we are going to talk about intensification. People need to feel the texture and the kind of delight of a place. Perhaps in the complexity of our times it gives us a window in terms of how we think about the world in which we live.

The knowledge about the “Metropole” or metropolis does not yet exist. We know the historical city very well but the metropolis is a new sub-urban substance about which we remain terribly naïve. In order to address this new substance, I think it is not enough to speak about “complexity” –we should speak about “complexities”. Of course, we are rather nervous about it because it implies we must imagine not one but multiple strategies.

For Paris, the economic, social, cultural and physical spheres of influence of the metropolis attract so many people that we should consider not just the 2 million official inhabitants of Paris, but a population of 12 million. This metropolis has a new name: the Grand Paris, Greater Paris, and the real question at hand now is how to build a metropolis for everybody, including this ungraspable population of commuters or temporary Parisians.

In order to address the question, former President of France Nicolas Sarkozy created a workshop, an experimental entity composed of expert teams, the “Atelier International du Grand Paris”. Unlike the many economic and urban research labs already working on the Greater Paris, this workshop is not about setting a holistic macro approach, but about generating several micro strategies that focus on people’s needs, targeting specific contexts and populations.

The DPA team decided to focus on the needs of a specifically metropolitan population we named the “uninscribed”. They are people who are attracted by the metropolis for its services but not its territory: they are for example expats who could easily move to other world cities, students who use Paris to learn but have no desire to stay, injured people who need the metropolis’ health or social systems to rebuild themselves, etc. To them, “home” is a countryside house rather than their city apartment, and yet willingly or not, they happen to be the pioneers, the first experimenters of the metropolis’ fluid world.

Faced with this fluid life that calls to new forms and temporalities of housing, the poorest 20% get the support of social welfare and are also less prone to extreme international mobility, while the richest 1% can afford the tools for a fluid personal real-estate management. However, the remaining 79% of the population are left to confront this new life on their own.

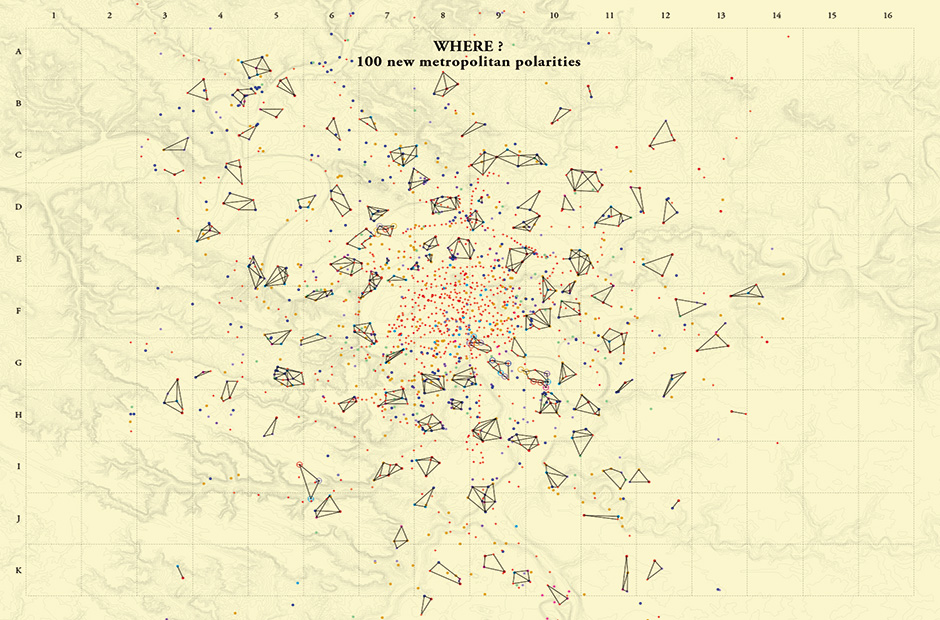

In order to deploy a new urban device adapted to the metropolis’ reality, we have tried to locate geographically the hotspots of metropolitan activity. To do so, we have intersected several data-bases relative to public equipment, labor pools of skilled workers, logistics and industrial centers. By empirically fixing an attraction threshold, we managed to reveal the geography of the Greater Paris metropolis for what it is: a discontinuous sub-urban substance looking like a cloud of connected singularities.

As we see it, the metropolis is to the traditional urban fabric what quantum physics are to Newtonian physics. For us architects it is a very exciting situation because in this field of physics the void is omnipresent and yet sees real physical connections between different elements. The resulting map is unsurprisingly much like a star map, in which constellations of local systems are often independent of administrative territories. Our programmatic device therefore aims at qualifying the various constellations as entities of the metropolis.

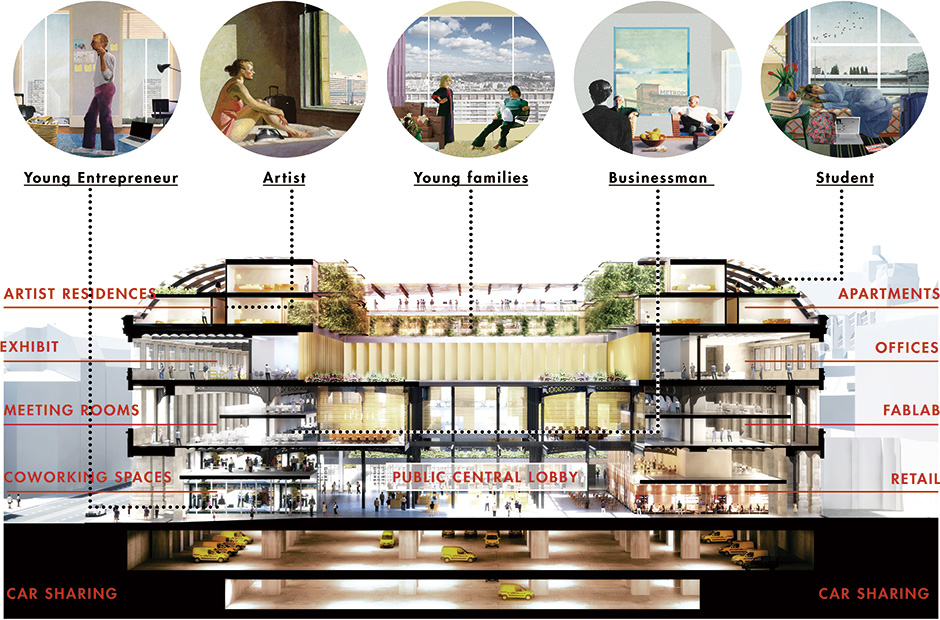

It is said that Paris is a city of 100 villages. By considering the metropolis as a meta-city of 100 meta-villages, we imagined the “Hôtel Metropole” as a program that would be implemented in each constellation. “Hôtel Metropole” sounds much like “Hôtel de Ville” (Town Hall in French) and indeed its most visible role will be to characterize meta-villages through a landmark architecture. In terms of function, it shall provide metropolitan services locally such as temporary housing for the “uninscribed” population, available spaces for co-working and other highly fluid work environments, places to gather for training, teaching, prototyping, etc. All of it would of course be highly connected to the internet in a smart sense, the building being considered as an urban resource that should be shared by a community and thoroughly optimized.

The Hôtel Metropole is a place where you could live and work and develop your personal life in the metropolis independently of whether you are in the heart of historic Paris or in a suburban constellation. The idea is to develop proximity and human interactions while accepting the metropolitan fact. We need not create a new modern movement. We can re-use existing architectural typologies but make them smart enough to build a network.

In other words, the Hôtel Metropole offers paradoxically a reference point in the fluid environment of the metropolis and a high-availability architecture, able to follow the fast pace of innovations and to swiflty adapt to new requirements. In many ways, it is a metropolitan extrapolation of the Mies Van der Rohe Crown Hall: a multipurpose available space to accommodate a community.

I think all of us in different ways try to discuss the idea of unpredictability. What is special about cities is the way in which you cannot actually plan what makes them great. What makes them great comes from all of the different collisions of unpredictability. This is I think the fundamental paradox of urban planning. Often a planner will say that all the tall buildings go over here and all the short buildings go over here as if we live our lives this way. If you are tall you only have tall friends. I think as we talk about all these strategies of intensification and densification what I worry about is that we will lose that sense of unpredictability and we will end up with a static city. That is my major concern as we see cities grow in the way that they are.

When I was appointed to work for the mayor of London, the only guidance that he gave me was to say that my job was to think about London and what made London unique and how we could make it better. We spent a lot of time studying other cities. The thing that struck was that actually the problems we were dealing with are common. The second thing was that most of our solutions were shared solutions. The third point was that speaking as a Londoner, I think I have more in common with a New Yorker or a citizen of Tokyo than I do with someone living 150 miles outside of my city in England. Therefore there is a common shared agenda between the cities that is very important. I was very struck by listening to the three presentations. What we are saying is largely the same thing, with a slight nuance or twist from the cultural context. That was really fascinating. The slight difference in the proposals for Tokyo against New York, Paris, and London were very interesting. That is where we can probably learn lessons from each other.

Tokyo for me is a fantastic city to control the large scale tall buildings and the small buildings very close together. This typology or morphology is a fantastic treasure. It is not so easy to combine this kind of scale with a huge network of avenues. In Paris it is very difficult to introduce this mixed city between tall buildings and small buildings. The answer is not one, but there are numerous answers about Metropole. We should not think of one certain global strategy. It is very inefficient if we do not worry about the adaptation and transformation from existing conditions. The existing conditions show the route to a successful transformation. The Metropole is in three dimensions and Tokyo is really in three dimensions. There is no discussion about that I think. The question is about the void. The empty space in the Metropole is a treasure because the void is for everybody. The void is an essential condition. And that is a void in the city, which is a possibility for everybody in the city to see something and embrace something.

Up until the present day, Tokyo has developed as a city by learning from London, New York and Paris. In 1888, Japan implemented its first urban plan after modernizing by emulating the renovation of Paris. Then in 1958, Tokyo modeled its metropolitan area planning on the Greater London Plan of 1944. As Japan achieved remarkable economic growth, Tokyo aimed to be more like New York, the world’s number one city. Over the next 10 years, I think each city will grow stronger under their respective urban models. I certainly hope that we can continue to maintain excellent relations and compete with each other as healthy rivals.